QUESTIONS: Where does money and value flow in the energy system? What needs to be paid for? How is this changing? How could this be done differently? How is the energy system financed? Who profits?

In the 2015 general election, Ed Miliband promised to freeze energy bills. This may have been a vote-winner, but from a systemic sustainable energy standpoint, it misses the point. This chapter explains why money underlies many decisions in the operation of the energy system, over a variety of timescales. Money is an attractive decision aid because it reduces a set of complex factors to one number. But does it represent real value?

This page gives an overview of money flows in the GB energy system. It then goes into more detail on three aspects, each on their own separate sub-page:

Key issues in energy system money flows

Money flows in the GB energy system are complex. This is partly because there are many different timescales involved. Domestic consumers pay bills monthly, with a fixed price per unit of energy. Suppliers buy that energy on a wholesale market, where the price of energy is different for every ‘settlement period’ – every half-hour for electricity, every day for gas. Mostly they buy that energy months or years in advance, the remainder the day or hour before. The wholesale prices are affected by all kinds of things – geopolitical events, strategic energy decisions made in other countries, the time of day, the weather. These events take place on different timescales again. Finally, the network, pylons, wires and power stations need investment, particularly as the system is transformed with new and low carbon technologies, and this has costs and value over decades, and decision-processes that anticipate as well as create the future.

In addition to the direct costs of energy, there are important indirect costs and benefits – which economists call ‘externalities’. These are impacts on wider society. For example, the cost of poor air quality for people’s well-being (and the NHS budget), the cost of burning fossil fuels on the climate (everyone’s future), or potential benefits of taking everyone out of fuel poverty

The GB energy system is run according to the principle of ‘cost-reflectiveness’ (or cost reflectivity), which is a core principle in the EU’s energy policy. This means that the bill paid by the end consumer is supposed to ‘reflect’ the specific cost of providing that energy to them, and if it costs more to provide energy to a particular consumer, that consumer should pay more for their energy. The intention is to achieve the elusive ideal of the competitive market in energy.

In practice there are problems with the principle of cost-reflectiveness:

- Cost-reflectiveness assumes there is a way of calculating exactly what is cost reflective – in practice the costs involved are simply too complex.

- Cost-reflectiveness is not inherently desirable – it is assumed that achieving it will indirectly lead to desirable outcomes such as low cost, reliable energy availability.

- This approach creates a set of incentives and outcomes which may go against other values such as environmental sustainability, access to energy for everyone, participation and democracy.

- The costs reflected tend to exclude externalities.

However, we need to pay for our energy system somehow, including maintaining/operating the current system, buying fuels, and investing in the zero carbon transition. The money that comes in eventually needs to cover those costs. Where that money comes from, the cost structure for consumers, and the transactions that take place within the system are all up for re-imagining.

Alternative approaches to energy provision, including those explored in the community energy sector, are often framed in terms of ‘business models’. From a commons perspective (see worldviews chapter), this framing is problematic, and I want to go back to the fundamentals of what we need for effective provisioning and sustainable usage of a resource. However, business models are of value conceptually. They have several components, but at their heart are the cost structure and revenue structure – the money that comes in, the money that goes out, and which of these is greater. Getting enough income over time to cover costs matters at every scale, from the GB energy system as a whole to small community energy schemes.

When it comes to long term investment, cost-reflectiveness becomes even more complicated. Building a zero carbon energy system requires a rapid, large investment in infrastructure. The value of this transition is largely in externalities to the energy system – avoided costs of climate change, improved health and well-being etc. By itself, the market is not good at delivering long term investment. Privatised network companies have a tendency to under-invest in long term infrastructure and innovation, and so the price control mechanisms regulated by Ofgem already include specific rules and incentives for innovation and investment. However, these are not suited to the transformational change required.

Long term investment decisions are partly about governance and decision-making processes, which are discussed in the chapter on governance and decision-making. This chapter focuses on the financial aspects.

Overview of GB energy system money flows

The total final expenditure on energy by consumers in 2018 was £128 billion. This includes spend in the transport sector (51%). Domestic consumers spent a total of £33 billion on energy (mostly gas and electricity). A total of £29 billion was spent by the industrial (13bn) and services (16bn) sectors. Source: Digest of UK Energy Statistics.

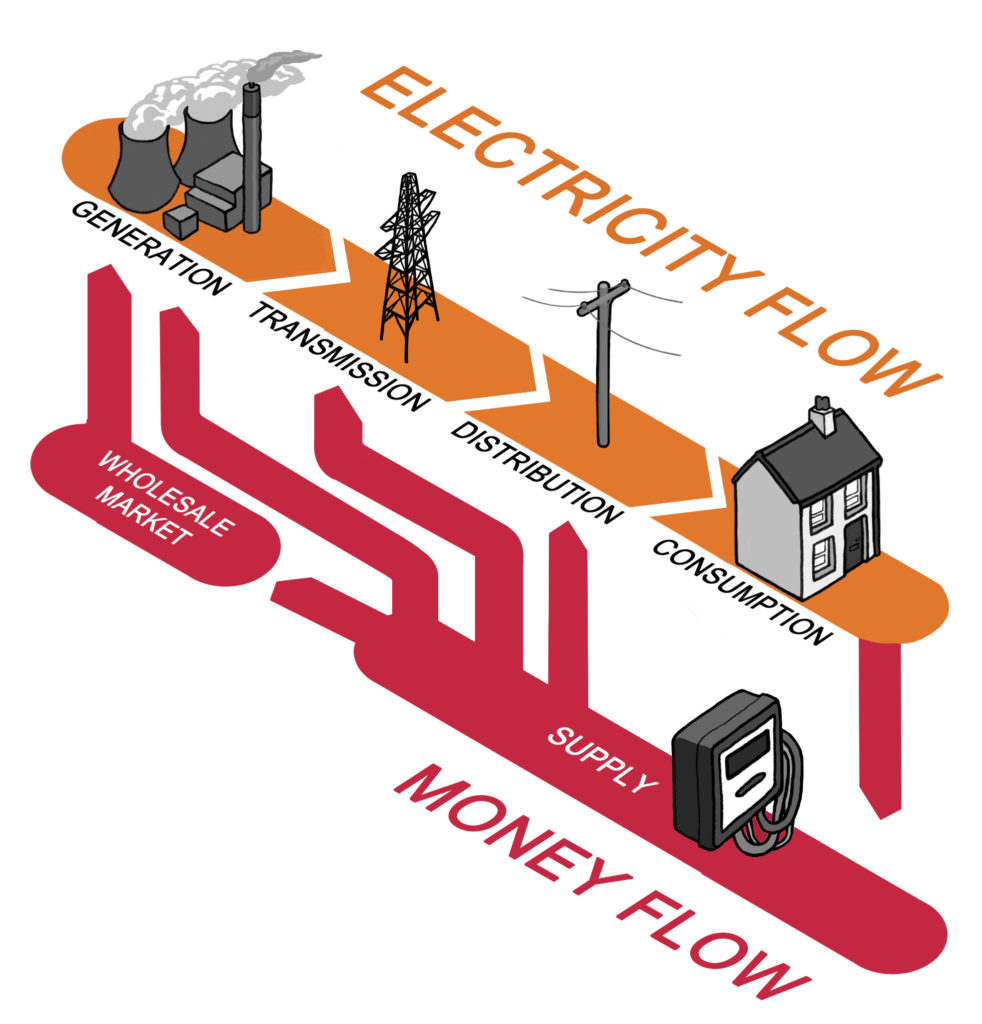

Electricity

In the electricity system, the final consumer pays a bill to the supply company. About a third of the bill is money that the supplier pays for the energy consumed over that billing period, which is bought by the supplier either from the electricity wholesale market or directly from the generator. Around a quarter is a charge paid to the regional DNO, and to National Grid Electricity Transmission (ET) for transporting the energy from generators to you.

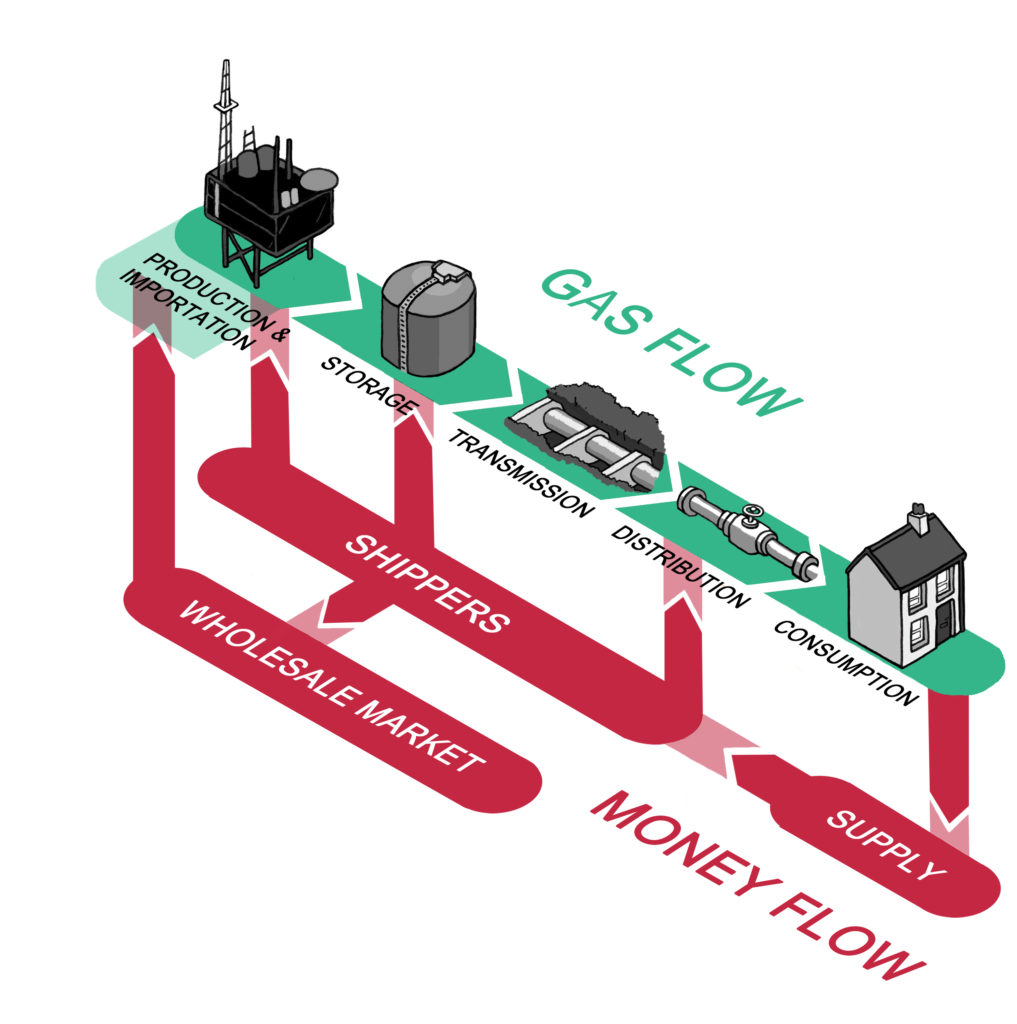

Gas

The money flows in the gas system are similar to the electricity system. However, there is an additional role, that of the ‘shipper’. The shipper is responsible for buying gas when it arrives in the UK, either directly from producers or from the wholesale market, and buying space in the transmission and distribution pipes to ship that gas to the consumers. Supply companies then buy the gas from the shippers.

More detail on GB energy system money flows is provided in three main sections: The first discusses where money comes into the system. The second discusses what needs to be paid for – money out. The third describes the way that the market is structured to link up money in with money out.