QUESTIONS FOR ENERGY DEMOCRACY: Who owns the GB energy system? Why does ownership matter? What alternative forms of ownership are being developed and proposed? How can changes in ownership be achieved?

Before going into detail on how the energy system is currently owned and could be owned, let’s think a bit more about what ownership is and why it matters:

- Ownership generally comes with the right to make decisions about/control an asset

- Ownership generally comes with financial benefits – the owner of an asset is able to both access its use value and extract value through profit/rent-seeking/re-investment.

The main value of ownership is therefore its secondary value, in decision-making and access to flows of money/value. However, it has its own primary importance in our society where property ownership is given high political and legal priority. Indeed, private ownership of property, particularly land and the means of production, is a fundamentally important institution (set of rules) to enable the effective functioning of markets.

In a capitalist economy where what matters most is how much we can buy and sell something for (exchange value), we are used to thinking of ownership as automatically conferring the right to buy/sell. However, it is useful to unpack ownership into distinct property rights:

- Access – who can connect to energy infrastructure (everyone)

- Withdrawal – who can withdraw units of energy (people with money)

- Management – who can manage the system (industry, regulated roles)

- Exclusion – who can decide those who have access, withdrawal and management rights (government)

- Alienation – who is allowed to sell parts of the system to another party (owners – but this could be limited through e.g. asset lock)

It is possible that different individuals or groups may ‘own’ parts of the energy system in each of these ways – i.e. as access or withdrawal, not both, for example.

What does democratic ownership mean? The current energy system is mostly owned by big publicly listed companies owned by shareholders, or state-owned companies from various countries. This is concentrated in the hands of neither the majority of users nor the majority of workers in the GB energy system.

Democratic ownership is taken to mean various different things:

- National ownership by the British State, assumed to be democratic through parliamentary processes

- Regional/local state ownership

- Worker/employee ownership of companies. There are various forms of legal structure that can be used for this

- Consumer/user ownership – co-operatives/consumer coops

- Communities – e.g. ‘the community energy sector’ – community co-operatives.

A report on alternative ownership models commissioned by the labour party gives a good overview and critical analysis of various legal forms of ownership that are available.

While ownership provides control and access to value, it is also closely tied to investment and capital. To own something under a private property market regime, one generally has to buy it.

- Community share offers are a key tool for the community energy sector

- The question of where will the money come from is key for the nationalisation agenda.

Different approaches to ‘democratic ownership’ can coexist. But, thinking about the detail of each is important. For example, how we can nationalise in ways that don’t just (re)create nominally accountable centralised bureaucracies. Or how the community energy sector can be part of wholesale democratisation of the system rather than just another small and parochial element of the status quo.

The current GB gas and electricity system is owned by private companies – mostly big multinational companies, many of which have fossil fuel interests, and state-owned companies owned by other countries.

Initially, energy (gas and electricity) networks were developed independently in towns and cities, sometimes by the local government, sometimes by enterprising wealthy individuals, and were a mixture of private and publicly owned. In some cases this provided a substantial income to local governments.

From 1926 to 1933, the national electricity network was constructed, connecting the local networks and requiring standardisation of voltages and frequency. The 1947 Energy Act led to the nationalisation of the energy system as a whole, and the creation of the Central Electricity Generating Board, which was responsible for all electricity system roles (more on these later) including generation, transmission, distribution, balancing, and supply.

The Electric Orchard

The early electric people domesticated the wild ass;

They had experience of falling off.

Occasionally, they might have fallen out of the trees;

Climbing again, they had something to proveTo their neighbours. And they did have neighbours;

The electric people lived in villages

Out of their need of security and their constant hunger.

Together they learned to divert their energiesTo neutral places; anger to the banging door,

Passion to the kiss.

And electricity to earth. Having stolen his thunder

From an angry god, through the treesThey had learned to string his lightning.

Burying the electric-poles

Waist-deep in the clay, they stamped the clay to healing;

Diverting their anger to the neutral,The electric people were confident, hardly proud.

They kept fire in a bucket,

Boiled water and dry leaves in a kettle, watched the lid

By the blue steam lifted and lifted.So that, where one of the electric people happened to fall,

It was accepted as an occupational hazard;

There was something necessary about the thing. The North Wall

Of the Eiger was notorious for blizzards;If one fell there, his neighbour might remark, ‘Bloody fool’.

All that would have been inappropriate,

Applied to the experienced climber of electric-poles.

‘I have achieved this great height’;No electric person could have been that proud.

Forty feet, of ten not that,

If the fall happened to be broken by the roof of a shed.

The belt would break, the call be made,The ambulance arrive and carry the faller away

To hospital with a scream

There and then the electric people might invent the railway,

Just watching the lid lifted by the steam;Or decide that all laws should be based on that of gravity,

Just thinking of the faller fallen.

Even then, they were running out of things to do and see;

Gradually, they introduced legislationTo cover every conceivable aspect of the electric-pole.

They would prosecute any trespassers;

The high-up singing and alive fruit liable to shock or kill

Were forbidden. Deciding that their neighboursAnd their neighbours’ innocent children ought to be stopped

Paul Muldoon

For their own good, they planted fences

Of barbed-wire around the electric-poles. None could describe

Electrocution, falling, innocence.

Rural Electrification 1956

We woke to the clink of crowbars

Maurice Riordan, reproduced with permission

and the smell of creosote along the road.

Stripped to his britches, our pole-man

tossed up red dirt as we watched him

sink past his knees, past his navel:

Another day, he called out to us,

and I’ll be through to Australia…

Later we brought him a whiskey bottle

tucked inside a Wellington sock and filled

with tea. He sat on the verge and told

of years in London, how he’d come home,

more fool, to share in the good times;

and went on the describe AC/DC, ohms,

insulation, potential difference,

so that the lights of Piccadilly

were swaying among the lamps of fuchsia

before he disappeared into the earth.

From 1979 there was a shift towards privatization, liberalization and deregulation, creating an energy market and the energy system structure that we have today.

Privatisation attempted to create a competitive market by splitting the single national system into separate parts along the supply chain. This ‘unbundling’ fragmented a system that needs to work as a whole to function effectively. Coordination is now done through market mechanisms rather than technical planning. The political ideology behind privatisation saw this as more efficient. However this fragmentation makes it difficult for the different parts of the system to act collectively to produce shared value – to reduce carbon emissions for example.

The transmission of gas and electricity are national monopolies, and distribution a regional monopoly, with a single company operating in each region for gas, and one for electricity (although these regions are not necessarily overlapping). The generation of electricity, production of gas and supply of energy offer possibility for competition. However, the companies that originally took ownership at the time of privatisation still dominate market share.

Due to the political and social importance of energy, and the natural monopoly nature of infrastructure, this privatised system is highly regulated.

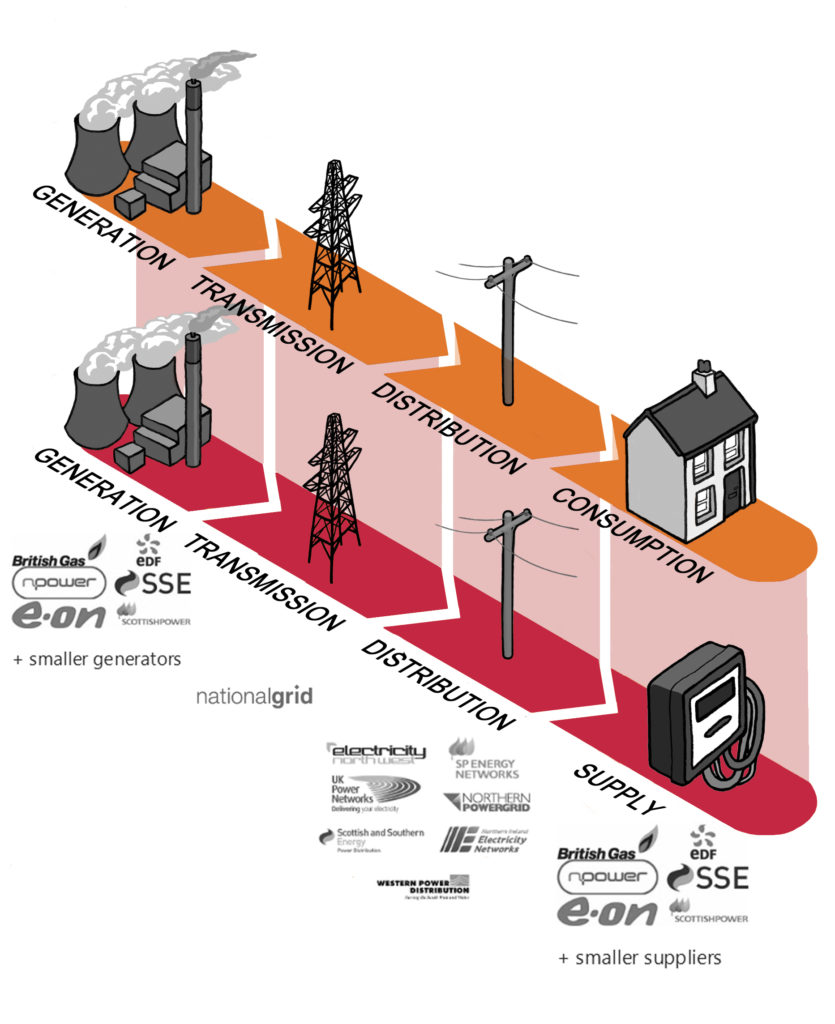

Campaign organisation We Own It propose a more democratic future, with different approaches to ownership proposed for each of the ‘unbundled’ sections of the system. This diagram shows the processes involved in the electricity system, but the principles also apply to gas which has a similar structure.

The chapter below gives more detail on current ownership for each of the ‘unbundled’ roles in the gas and electricity system.

It also describes some projects that have implemented different forms of ownership which look more like the ‘we own it’ proposal.

It is important to understand that:

- Many of the same companies dominate multiple roles after privatisation. They tend to have decision-making and political power (link to governance section), have fossil fuel interests, and stand to lose something from a more democratic energy system.

- The governance of the system as it is now limits the scale and scope of the alternative ownership models. Some of these have to bend over backwards to fit into existing rules, which can make them overly complex. [second sentence here is green]

- Making system-wide changes to ownership such as those proposed by We Own It would involve national scale political will. [blue]

Electricity

When the electricity system was privatised, it was split into separate licensed roles: generation, transmission, distribution and supply. These roughly map onto the physical infrastructure, with the exception of supply, which is a retail and billing role.

The basic roles in the UK electricity system is shown below.

In addition to these four main roles, there are ancillary (support) roles that also have organisations associated with them. These include:

- Wholesale market

- System operator

- Storage

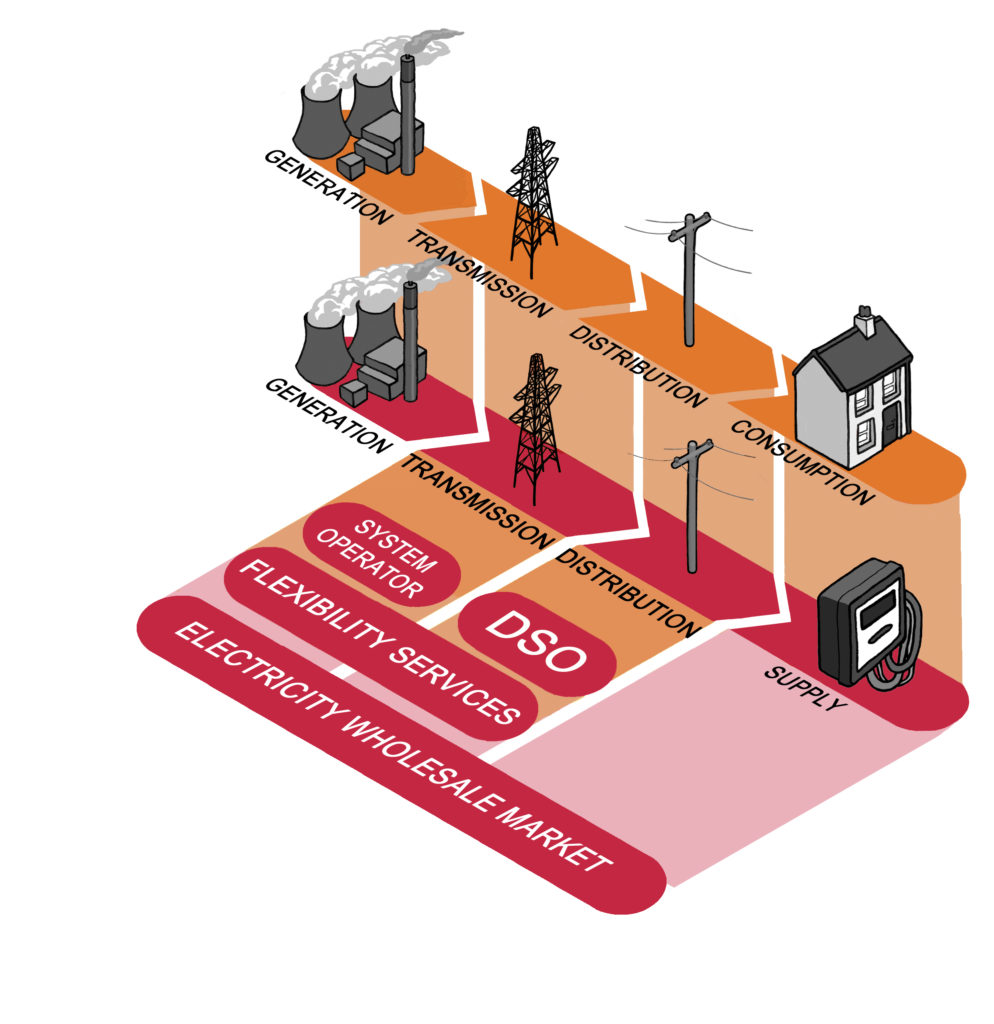

- Flexibility service providers

The need for flexibility means new organisations are entering the system. They own and operate storage, provide ‘demand response’ or ‘flexibility’ services (i.e. various ways of changing when electricity is taken from the grid), or more integrated energy services. Some of these services already exist in some form and are expanding into new roles, others are squeezing in at the edges of what is permitted in the current regulatory framework.

Supply (retail)

Supply is at the end rather than the beginning of the electricity system as presented in the physical infrastructure chapter, but is discussed here first because this is the part of the system that is most familiar. Suppliers sell electricity (and often also gas) to consumers. The ‘Big Six’ energy companies are supply companies.

Suppliers do not own significant infrastructure as such (unless it is through another arm of their company). They make their money by trading – they buy electricity on the wholesale market, and sell it to customers. The supplier is responsible for billing customers, but does not own the meters.

This is a competitive market which is dominated by the ‘Big Six’, but where there are also a growing number of smaller suppliers.

The market share of the Big Six has reduced substantially between 2004 and 2019, as shown below:

Five of the six supply companies inherited customers from the Regional Electricity Companies at privatisation, as shown in the maps below. Centrica (British Gas) did not inherit market shares in electricity supply, but inherited all of the gas supply customers at privatisation, which put it in a strong position when it entered the electricity market in 1998. The market shares of the big six energy supply companies may still follow the geographical pattern below – if anyone has statistics showing this please get in touch!

Parent companies and ownership

The parent companies that own the big six are:

- British Gas, a subsidiary of Centrica, a multinational company based in Windsor, UK

- EDF: Electricite de France – company with majority share held by the French state

- e.on: investor-owned energy company, based in Essen, Germany

- SSE: public listed company, HQ in Perth, Scotland

- NPower: associated with RWE, e.on and Innogy, with various mergers and acquisitions etc.

- Scottish Power: owned by Iberdrola, a Spanish company based in Bilbao, Basque country.

Most of these companies are listed on the stock exchange. Some digging may reveal who the major shareholders are, where they are based etc.

Democratising ownership in supply

This is the most well-known part of the energy system, as it is suppliers that customers interact with by paying bills, and demonise as the ‘big six energy companies’. That makes the supplier role an attractive and symbolic role to attempt to bring into more democratic ownership. However, it is a particularly difficult and limited place to create alternative forms of ownership because it is highly regulated and competitive. And most people don’t realise that public or community ownership of the natural monopoly elements of the system (transmission and distribution) would have more impact.

Public ownership in supply

Several local authorities have considered setting up a local energy supply company. There are two main options: collaborating with a licensed supplier to provide a local-government branded version of their tariffs or setting up a fully licensed supply company.

Nottingham and Bristol city councils have set up fully licensed supply companies. This was a bold move but it has proved to be difficult to generate profits. Other local governments in London and Manchester have been put under pressure by activists to develop municipally owned energy supply, but have chosen not to. The financial and democratic governance arrangements involved in these actual and proposed projects are discussed in more detail in the chapters on money flows and on governance and decision-making.

Community ownership in supply

Selling electricity to consumers is a vital piece of a community energy system. However, it is not legal without a supply license. It is expensive and onerous to get a license – so much so that it is outside of any community energy group’s reach.

This is partly because in GB the supplier is responsible for balancing, due to choices made during privatisation. This responsibility comes with high costs and uncertainty over future costs, for reasons discussed in more detail in the section on money flows. In some European countries, balancing is a separate licensed role to retail, and energy retail co-operatives have been able to enter the market and flourish. On the other hand, the balancing role is much more monopolistic in these countries.

Community energy co-ops could be a vital part of a wider ecosystem of democratic roles in the energy system. A commons-based system (see worldviews section) is one where provision and consumption take place within one institution – and access to the ‘supply’ role is essential to achieving this.

This would allow:

- [bullets green]

- Bulk-buying of electricity at a discount price

- Creating fair tariffs for people on prepayment meters

- Creating tariffs that incentivise energy efficiency and encourage people to moderate their consumption

- Providing a stable and viable price for community based energy generators, to make those business models viable

- Enabling communities to benefit financially from providing flexibility services

- Pooling renewable energy resources within a community

- Having a cheaper price for local energy which avoids transmission losses

- Demonstrating real ‘member benefits’ for community energy projects, and making these organisations relevant to more than just people who can afford to invest money.

Some community energy groups have attempted to access some of these benefits through the development of flexibility services, as discussed below. Private wire arrangements (described under ‘democratising distribution’) also provide an opportunity to sell electricity to households by being exempt from a license. It is important to note that this can result in freeloading on the national grid and not contributing.

Generation

The power stations generating electricity in GB are mostly owned by ten large companies. Despite the separation or ‘unbundling’ of generation and supply activities, many of the supply companies also own generation – through separate legal entities of the same company.

The power stations that were owned and operated by the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) in the national energy system pre-privatisation were sold to private companies in stages during the time of privatisation. In 2019, seven large companies dominated 72% of the electricity generation market

Parent companies and ownership

- EDF: Electricite de France – company with majority share of the French state

- RWE: associated with E.On, NPower and Innogy – various mergers and acquisitions.

- SSE: public listed company, HQ in Perth, Scotland

- Drax: owned by the Drax Group, who also own supply companies Opus Energy and Haven Power, who mostly supply businesses.

- Uniper: formed in 2016 to separate out fossil fuel assets previously owned by e.on.

- EEX

- Scotish Power: owned by Iberdrola, a Spanish company based in Bilbao, Basque country.

- Orsted

Notice how many of these overlap with the ‘big six’ supply companies listed above.

Smaller distributed generation of energy is also becoming increasingly important. This provides an opportunity for more democratic and small-scale ownership. The size of the infrastructure itself shapes ownership and power relationships.

Democratising ownership in generation

Community generation co-operatives

Generation is the easiest thing for community projects to set up. The first community owned wind turbines in the UK were set up in 1996 by Baywind, in Cumbria. This was modelled on a successful project in Scandinavia. People involved in Baywind then set up Energy4All, a development company which helps others do the same thing.

In this ownership model, a co-operative, which is a specific form of legal corporate structure, owns the wind farm or other electricity generation. A co-operative is designed to be democratic, with key decisions made by the members who have equal voting rights per person (unlike a typical shareholder–owned company where votes are allocated based on the amount of money invested). There are several legal structures available, including:

- [green bullets]

- Community Benefit Society, or ‘bencom’ – where benefits go to members and the wider community

- Co-operative – where the benefits go to members only

The aim of local ownership is to give local people a say in energy developments happening on their patch, and to allow local people to invest and financially benefit from the income generated by renewable electricity, either individually or as a community or both. In other countries, particularly Denmark, there was regulation requiring community or local individual ownership of onshore wind, which was associated with much greater public support for this technology and less protest against the visual impact. Part of the reason that people in England have been so strongly opposed to onshore wind is that they see the local landscape changing in a way that brings no local economic benefit or control.

The conditions for wind power are particularly good in Scotland. In the mid-late 2000s, the Scottish Government and particularly the Highlands and Islands Enterprise set up Community Energy Scotland, a social enterprise and charity aiming to support communities to set up locally owned energy generation. Many of the projects established in Scotland have provided substantial income to local communities.

In 2009, the UK government launched the Feed in Tariff – a guaranteed subsidised price for electricity from renewable energy – and this made solar PV generation financially attractive. The technical and regulatory process for putting solar PV panels on buildings was much more straightforward than wind farm development, so many new community energy groups were set up to take advantage of this opportunity. Most of these used a ‘bencom’ structure.

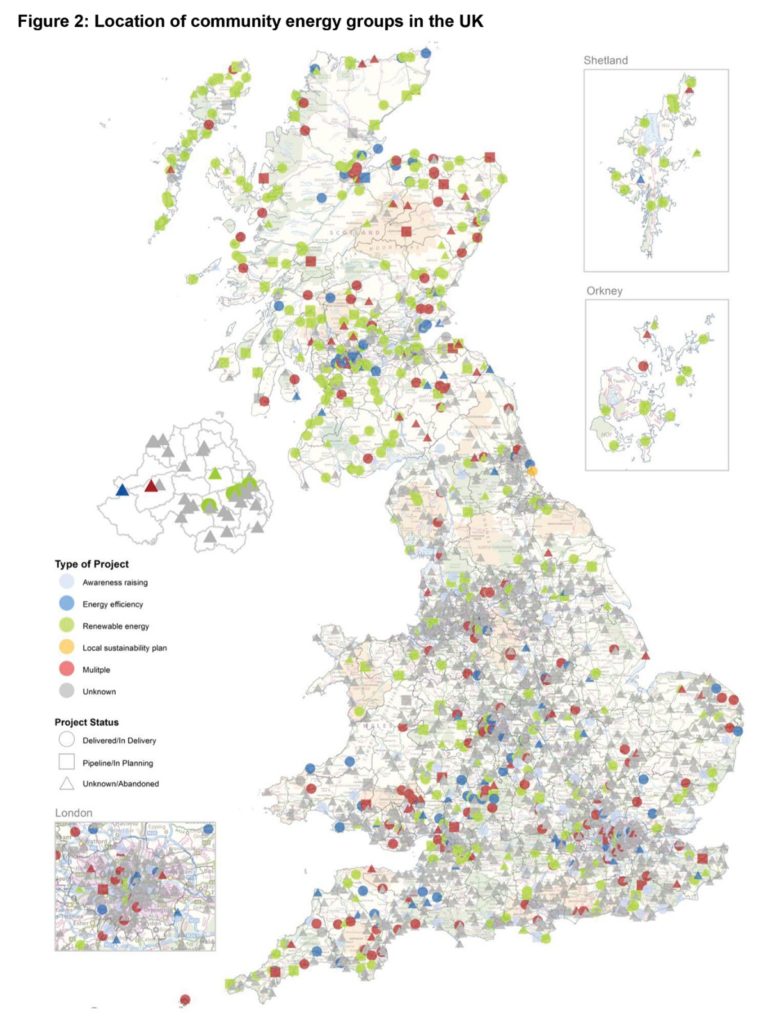

The boom in community energy projects in 2010-2015, which coincided with ‘big society’ policies at national government level, led to a lot of policy and academic interest in ‘The Community Energy Sector’. Community Energy England was also set up during this time as a representative body for the sector.

In 2014 the Department of Energy and Climate Change published a Community Energy Strategy, which included the following diagram to aid in definition and identification of community energy projects.

And the following map of community energy groups active since 2008, across a variety of project types, including raising awareness, energy efficiency, renewable energy and local sustainability plan.

Renewable energy generation-based community energy groups typically used a community investment business model as shown in this diagram made by Forum for the Future, with a community share offer at the heart of raising capital.

The reasons to invest in a community share offer are set out clearly in this short video by Bristol Energy Co-op.

The social and environmental value, and opportunity for widening democratic participation provided by a community energy project varies. Most community energy projects care about all of these matters, but prioritise them to different extents. This is partly about the level of financial return going to investors compared to the community fund, the minimum investment level which excludes people who can’t afford it, and the other approaches to inclusion that are embeded into the projects.

Domestic and private ownership of generation

The energy co-operatives described above represent collective approaches of ‘people’s’ ownership of electricity generation. Ownership by households, families and other small-scale users of energy is another form of democratisation. The Feed in Tariff enabled many households to put solar panels on their roof. Farmers installing wind turbines on their land are another form of consumer-controlled ownership of generation.

A key feature of private ownership is that it is ‘behind the meter’ – the electricity can be used by the consumer before it flows onto the grid. This saves the consumer money. Timing is crucial here – if the electricity is generated at times when it is not consumed, the benefit to the consumer may be lost, depending on metering arrangements.

Storage

Confusingly, storage of electricity is categorised as ‘generation’ in the regulations. This means that DNOs and the Electricity System Operator (ESO) are not allowed to own and operate storage, due to the ‘unbundling’ of system roles which aimed to achieve a competitive market. Given that DNOs (or DSOs), and the ESO are responsible for grid capacity (i.e. how congested the ‘road’ is getting) and balancing (i.e. is the amount of electricity generated matching the electricity used), and that storage can help regulate these issues, this is a missed opportunity for operational smoothness.

Pumped storage

Historically, the only major electricity storage was hydropower based ‘pumped storage’ operators in Wales (Donorwig, Ffestiniog).

- Engie Power – Dinorwig and Ffestiniog pumped storage – in Wales

- Drax – Cruachan – pumped storage in Scotland

Batteries

New forms of storage, particularly batteries, are now being built next to renewable energy generation to smooth the times that wind farms or solar farms put energy onto the grid. Storage is also being built at strategic locations on the energy network (substations), to help address pinch points in the flow of electricity. Some companies involved in this include:

- Pivot Power – London based focused on batteries at national grid substations

- Aura Power – Bristol based multinational – focus on batteries co-located with renewable energy

image credit Robert Ashworth, creative commons

image credit Askjell (creative commons CC BY 2.0]

Democratising ownership in storage

Community and home business models for storage are discussed later under ‘flexibility’.

Peaking plant

In addition to storage, we need electricity generation that can quickly respond to peaks in demand, called ‘peaking plant’. New peaking plant are being built, incentivised under the ‘capacity market’ (see money flows chapter). Some of these are owned by established energy companies, some are new small companies set up specifically for this. These are often small diesel or gas generators, and are controversial as they use fossil fuels and are not always as energy efficient as bigger power stations. However, the environmental impact of these should be compared with the full environmental and social impact of batteries. It may be that in future, hydrogen based peaking plant provides a valuable solution.

Transmission

(TNO – Transmission Network Operator)

The private, multinational company National Grid owns and operates the high voltage transmission network in England and Wales. In Scotland, two companies, Scottish and Southern and SP Energy Networks each run the transmission network in different areas, and in Northern Ireland this is done by Northern Ireland Electricity Networks.

Parent companies and ownership

- National Grid

- Northern Ireland Electricity Networks

Democratising ownership in electricity transmission

There is no actual alternative ownership in electricity transmission currently. There are proposals by We Own It and by the Labour Party to bring it into public ownership. Academic David Hall has analysed the financial costs and benefits of doing this, discussed in ‘money flows’ section.

System Operation

(TSO, Transmission System Operator)

The National Grid has an additional role, which is separate to the Electricity Transmission (ET) role described above. This is called the Electricity System Operator, or ESO (a video explaining this role is available here: https://www.nationalgrideso.com/about-us/what-eso-and-what-does-it-do). While the TNO role involves maintaining the physical infrastructure of the transmission network, the ESO is a temporal balancing role that maintains the electricity system’s voltage and frequency at an appropriate (regulated) level. In Great Britain, this role is done by National Grid, across England, Wales and Scotland. In Northern Ireland, this role is done by SONI.

Parent companies and ownership

- National Grid – see above

- SONI

New approaches to system operation

The Exeter university research project iGov proposes that the System Operator role should be in public ownership rather than owned by a private company, and that it should be changed to an integrated system operator role – including electricity, gas, heat and transport energy. This is described in more detail in the chapter on governance. Integration across different energy vectors could increase efficiency and effectiveness from a technical point of view.

Distribution

The lower voltage ‘distribution networks’ are owned by Distribution Network Operators, or DNOs. There are 14 different Distribution Network regions in the UK, which are owned and operated by six different companies.

Parent companies and ownership

- Electricity North West Limited

- Northern Powergrid

- Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks

- ScottishPower Energy Networks

- UK Power Networks

- Western Power Distribution

In addition to the main DNOs, there are some independent distribution networks, or iDNOs. These mainly offer alternative connections to new developments, and are regulated under different license conditions and codes (see governance layer). For small self-standing sites, it is possible to operate the local distribution network without a license. This ‘license exempt’ network is called a ‘private wire’. The private wire arrangement permits sale as well as distribution of electricity.

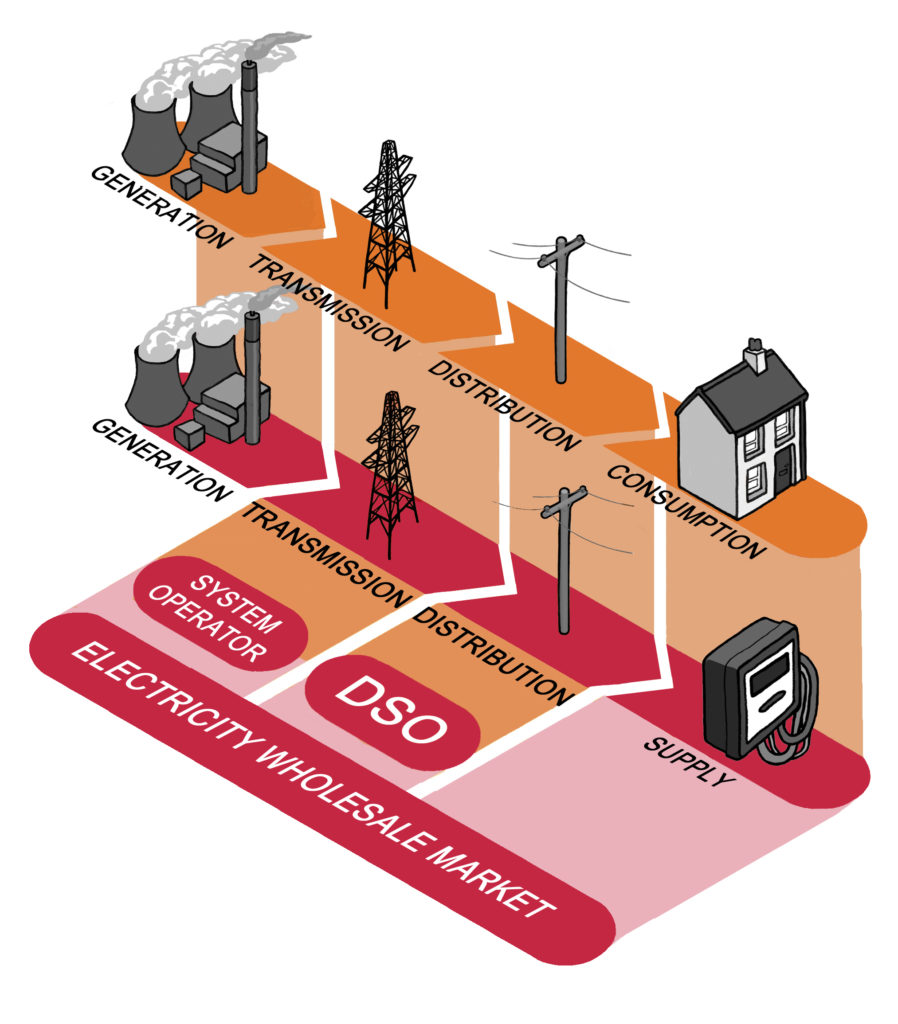

Distribution system operator

As the electricity system changes, local distribution networks need to take a more active role in managing the network, taking on some local responsibility for balancing. This new role is called the “Distribution System Operator” or DSO. Western Power Distribution, the DNO for the South West and West Midlands, has produced an animation explaining this. This is part of a series of explanatory animations by Regen.

Democratising ownership in electricity distribution

In Germany, the distribution network operator role is a franchise, similar to the UK train operator system. The franchise comes up for renewal periodically at which point there is a competition. Activists have attempted to buy-out the electricity distribution network in many places, and in some cases have been successful. In the UK, the opportunity for buy-out of the distribution network is not available. There is currently no public or community ownership of the distribution networks.

Flexibility service provider

This is a non-regulated role in the energy system, and does not require a license.

Commercial aggregator

There is already a system for big energy consumers such as supermarkets to be paid for switching off large amounts of energy consumption – such as freezers – when requested at peak times. This takes place through ‘aggregators’ – companies who bring together or aggregate the ‘demand response’ of several energy users and contracting this to national grid – acting as an intermediary. Commercial aggregators are listed on the National Grid website. Some of these are also suppliers and/or generators, others are specialist flexibility service providers.

Democratising flexibility

Currently flexibility and demand response does not extend to households. However, when smart meters are rolled out to all homes, this will become increasingly possible. There are broadly two approaches to this:

- [blue colour] time of use tariffs – where the price of electricity varies depending on when it is used

- providing flexibility services to DSOs or the SO, for a fee, similar to the commercial aggregator role.

There is a lot of talk about flexibility for households, and ideas for community energy groups being part of this. In practice, flexibility services provided by a community energy group would work best as part of a local energy system providing multiple energy services.

One model of a community energy aggregator, developed by BuroHappold Engineering in 2013, involves a ‘community energy aggregator’ acting as an intermediary between localised smart electricity microgrids in neighbourhoods and the national electricity system. This was informed by polycentric and commons governance approaches with nested layers of governance, each activity taking place at the appropriate scale (e.g. community relationships at the neighbourhood scale, billing and technical services at a larger scale).

In 2018, in the context of the DSO transition, some DNOs started developing local flexibility markets and publishing prices for local flexibility services. Carbon Co-op and Regen developed the concept further and reviewed the legal and regulatory context for an ‘Energy Community Aggregator Service’ (ECAS). They similarly proposed a federated approach:

“ECAS would operate aggregation and technical platforms and host information in the form of a data co-operative, effectively giving householders ownership of their own data and a share in any benefit from how that data is used. A federated aggregator achieves both scale and a locally specific focus, and the community energy sector has a number of strengths that are valuable to the model.”

While the community energy aggregator model described above is still on the drawing board, some community energy groups have developed actual projects to provide flexibility or energy services. Most of these involve collaboration with a licensed supplier. This is not necessarily lucrative for the supplier, so projects in this format may only be able to exist as demonstration projects, rather than models that can be replicated. They also tend to be extremely complex to get around regulatory requirements that prevent them from working in more straightforward ways.

Examples include EnergyLocal which pools renewable electricity in a local community; the Sunshine Tariff, which offered cheaper electricity when the sun is shining; and Tower Power, which shares electricity within a tower block.

Storage as flexibility

A big part of flexiblity provision is storage. Bristol Energy co-operative explored a community funded battery in a new housing devleopment. Bath and West Commnity Energy are recruiting volunteers for a flexibility pilot project using hot water heating.

Wholesale market

The electricity wholesale market is operated by Elexon. This is a not for profit company owned by National Grid. Elexon is the administrator of the Balancing and Settlement Code (BSC), discussed in the governance chapter. The operation of the wholesale market is discussed in more detail in the money flows section.

Gas

Traditional configuration

Production and importation

Various companies own and operate gas extraction and import, via major ports.

Transmission

This is owned and operated by National Grid, the same company which owns and operates the electricity transmission in England and Wales, and the transmission system operation in Great Britain.

Distribution

Similarly to the electricity distribution networks, gas distribution is carried out in regional monopolies. As with electricity, there are also independent gas transporters

Supply

This is done mostly by the Big Six energy companies. They, and many of the smaller companies, offer ‘dual fuel’ tariffs, where consumers can purchase gas and electricity from one supplier. Some renewable energy companies offer “green gas” tariffs as well as green electricity tariffs.

Lessons for Energy Democracy

- Supply is not the most effective place to act to democratise the system, although it is often targeted as it is visible to people who aren’t energy system geeks. Natural monopolies of distribution and transmission may be more useful target for public ownership.

- However, sale to consumers is an important role to enable access for creating energy commons. CE participation in supply is not feasible because regulation is too onerous.

- In some EU countries, balancing is a separated role from supply. This makes CE access to supply market much less onerous. This could be a key place to act on the system.

- There are opportunities for democratisation of newly emerging energy system roles such as storage and flexibility, before they become consolidated with corporate ownership.